Pedro Barros Is Building Skateparks With Beer Money

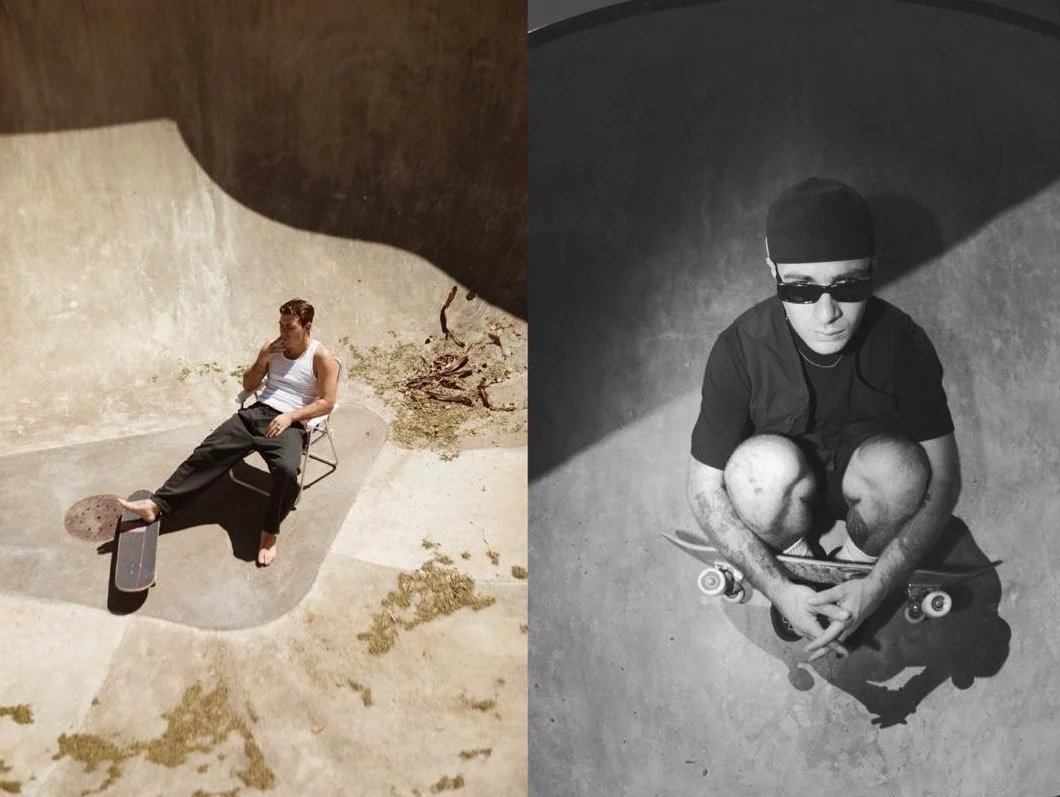

Portraits by Tauana Sofia, other Images Courtesy of Andre Barros

If Jake Phelps, the late editor of Thrasher magazine, gives you his blessing and reassurance that “you’ve got it all figured out” before the age of thirteen, then you must be doing something right.

Brazil’s Pedro Barros, Olympic silver medalist and 2018 Park Skateboarding World Champion, knows the feeling.

“Phelps said, “Pedro, just remember, always, that you got RTMF and you can always say, ‘Fuck you,’ to the rest. You have your family to come back to. You got your roots, you're good, you’re set,” Barros recalls.

What did Phelps see in Barros? And more importantly, what is RTMF? The answer lies in Barros’ hometown of Florianópolis, the capital and largest city of the state of Santa Catarina, in southern Brazil.

The story begins before 1995, the year that Barros was born. At that time, his father, Andre, had recently relocated to Florianópolis from Brasília. After discovering surfing on a trip to California at age 17, Andre returned to Brazil knowing that he would leave the country’s land-locked capital in search of waves. When he settled on the small island, chosen for its proximity to the water and cheap cost of living, Andre fell into a small, yet tight-knit, community of like-minded people.

Among those individuals was Léo Kakinho, one of Brazil’s pioneers of bowl skating in the 1980’s. Kakinho invited OG Alva riders Dave Duncan and Eddie Reategui, as well as up-and-coming Brazilian Bob Burnquist, to skate the wooden mini-ramp and full, concrete bowl in the neighborhood of Floripa, where Barros lived.

“Léo introduced me to skateboarding by leaving his skateboard at my house. I was a baby thinking it was just a toy, and couldn't let go of it. So skateboarding was in my life from a really young age,” Barros said. “By accident I was born into a place with this crew of people that lived a lifestyle like the core scene of California. You know, the guys who really started it all.”

But why skateboarding? Barros could have just as easily gone down the route of pursuing surfing, like his childhood friends Yago Dora and World Champion Adriano de Souza. When living in Australia between the ages of six and nine, Barros got comfortable surfing world-class point breaks, where he was pulling into microbarrels and attempting airs. Upon his return to the local beachbreak in Floripa, one of the heaviest in Brazil, the unforgiving wave taught him a lot about humility.

“I'm not as comfortable as I am in the air, or on land. In the water, I feel really vulnerable. I also had reached a point with skating where it made it more difficult to be any other thing. There was no kid my age that was coming close to what I was doing at the time. Also, at the time, John John [Florence] was coming up and I would see videos of him and think, ‘No way! How am I going to compete with this guy who lives in Hawai‘i?’” Barros said.

With his heart set on skating, Barros grew in sync with the scene that was beginning to blossom in Florianópolis. The bowl, which was located at his godfather’s house that doubled as a hostel, became the main attraction. Half a mile from the beach, that property was the hub for surfers, skaters, and artists to barbecue, drink beers, and play music together. This crew, dedicated to growing the scene while promoting respect for the community, came to be known as RTMF. Urban lore has it that Fabio “Binho” Nunes used the phrase, “Rio Tavares, motherfucker,” to describe the neighborhood to a visiting Californian, who returned on a future visit with T-shirts and hats featuring the acronym.

With time, word was getting out about “Magic Island,” as Florianópolis is known to the locals. Gradually things began to get unsustainable. Visitors, drawn to the idea of surfing, skating, and partying, flooded to the region and expected to be accepted with open arms. The hostel Barros’ godfather owned was overrun with tourists, who seemed to only take but never give.

“All of a sudden people were coming in [to the community] eating your food, taking beers, and being rude to your kids, Then you have to start regulating. That happened a lot of times, in the water too, having to be a dick. Some people would think we were a crew that wouldn’t let anyone in, but that wasn't the case. We are a family, not a crew. Of course you are not going to arrive and get in our house, like that. It takes a little bit. You aren't going to let a stranger into your house,” Barros said.

Barros, who was around 18 at the time, brainstormed with his father about how they could support the community while also accommodating outsiders, who were clearly enthralled with the region. The pair decided that a beer company would fit the bill. After visiting Bali and witnessing Bintang’s omnipresence and influence on Indonesian culture, the Barroses thought they could recreate the same model in Florianópolis.

“My dad and I agreed, [we thought,] ‘We all drink beers and the whole RTMF crew spends a lot of money on Heineken; so fuck it, let’s make our own beer!’ There was nobody in skateboarding that had a beer sponsor, so pretty much everyone in the industry could support our company. And it was a product that didn’t have any conflict with my sponsors at the time,” Barros said.

Deciding to keep the brand’s roots in skateboarding, the Barroses dubbed their new endeavor LayBack, in honor of the classic vert maneuver. Next steps involved diving into the beer world, developing a recipe, and teaming up with local brewmasters to turn their idea into a reality.

From the onset, the brand’s purpose would be to give back to skateboarding–15 cents of every beer would go directly to developing a larger skateboarding infrastructure in Florianópolis. Funding for the company came from X-Games winnings; Barros won medals, including six gold, across ten events in the “Skateboard Park” division between 2009 and 2016. In addition to the beer itself, Barros put money into amateur contests and a skate team that would travel both in and out of Brazil, producing videos along the way.

As exciting as it was in the beginning, Barros eventually saw that LayBack would be difficult to make profitable in the long term. In order to reach that realm, he would have to purchase his own brewery, rather than outsourcing his recipes to existing brewers, and ramp up production to a much larger scale. Instead of expanding Layback in that direction, he decided to regroup with his dad to think about a more creative solution to the situation. From that conversation, LayBack Parks was born.

The concept between LayBack Parks is to create a network of brick-and-mortar locations that encapsulate the energy and experience of Barros’ godfather’s backyard bowl. Although not every location features skateable objects, they all offer guest accommodations, a bar that serves LayBack’s varieties on draft, and dining options. Keeping skateboarding at the forefront of the brand, Barros helps design skateparks utilizing signature LayBack coping block around Brazil as well. By zooming out from only focusing on beer, he now hopes to recreate the spirit and essence of RTMF and amplify it across the country.

“LayBack is just a company for us to be able to live, and introduce others to this lifestyle. Sometimes the audience might not connect with skateboarding or surfing 100%, but they connect with beer, food, and rock and roll,” Barros said. “I think that is pretty much what it is now–it’s a lifestyle company whose product is the Fountain of Youth. We just try to do shit that makes us feel happy. That is the main feeling we are trying to create–the feeling of being young.”

As of today, LayBack has expanded outside of Florianópolis and developed 16 skateable LayBack Parks around the country. Since the brand’s inception, Barros’ goal is to use profits to give back. In a country with so much obvious wealth and health disparities, he feels that it would be selfish not to help others along the way. Starting with his local community, he wants to start a movement to make the world a more community-driven place.

“A couple kilometers from here, there are favelas where kids are dealing drugs to survive. Why aren't we helping each other more? Why are people having to run away from their countries because they are at war? Why is this going on right now? OK, it’s about the power and the money. But what does that really give you in the end? If you are healthy you don't need anything else. We still have so much to grow, I guess, as a global community,” Barros said.

It’s no wonder that people want to travel to Florianópolis to experience the LayBack lifestyle, because it’s authentic. Barros attributes it to an overall harmony. It comes from all sides–the community, the island living, the water, the nature, and the inhabitant’s heartfelt desire to protect it. Differences are respected and put aside for the greater good of all. In doing so, everyone gets to live a better life, not just the privileged few.

“It doesn’t matter if you are a world champion or a local fisherman; you both look each other in the eye, say, ‘What’s up?’ and show respect to one another. Even if it's an animal or a tree, you respect it. These have been the values here, and I feel like obviously because of the passion of the people in this area, they keep that philosophy going,” Barros said.