Revisit: Harmony Korine: This Mess We’re In…

words by kate williams. photography by ari macropolous.

this article originally appeared in monster children issue #27.

We are the kids in America.

I remember my adolescent years as idyllic, the stuff of teen movies. But there are other memories that don't seem to fit in with this picture. Nights spent driving aimlessly around my hometown of Wichita, Kansas, gathering up yard ornaments and trash to throw off a bridge. The time I mistook a stabbing five feet away from me for a mosh pit, and stories of house parties that ended in shootings. The heft of an old rubber tire as two 15-year-old girls hoist it over a rail, and the split second of silence as it falls, breaking the sound of buzzing street lights with a splash as it hits the river below.

I had not expected to be able to watch Trash Humpers, Harmony Korine's latest full-length film. Styled as a VHS tape supposedly found in a ditch, Trash Humpers follows a group of people (including Korine and his wife, Rachel) who wear grotesque elderly masks and terrorize a small town. They torture dolls, engage in group gropes with obese women in lingerie, destroy electronics equipment, tap dance, fellate trees and, yes, hump trash. But surprisingly, I made it through all 77 minutes and 37 seconds. Maybe it's the masks, but Trash Humpers is even more surreal than Korine's past works Gummo and Julien Donkey Boy, and therefore less shocking and less uncomfortable. There is a scene with a cat, but it is not skinned, drowned, or decaying—it is simply walking through the yard.

What there is in Trash Humpers is a lot of silence, a lot of scenery, and this is what kept me watching. Korine's work has always been laced with profound beauty, genuine stunning moments sandwiched in between scenes of brutality, and in this realm, Trash Humpers is no different. A desolate soccer field, illuminated by floodlights and filled with the buzz of cicadas. A dark suburban street and the soft rustle of the wind through the trees, deserted alleys and paths with the chirp of birds and the bark of a dog, and empty parking lots. So many empty parking lots.

To any kid who grew up in small town America—or any place where the nearest city was far enough away that it might as well have been Mars— and filled their nights with too little to do and too much time to do it, these sights and sounds are home. This landscape breeds destruction and violence like forgotten dog food breeds flies. So, sorry America, the consequence-free melee that is Trash Humpers is as just as much your story as The Blind Side.

When I catch up with Harmony Korine, it is 10am on a Saturday morning in New York. Korine, his wife Rachel, and their seventeen-month-old daughter are in town to visit Korine's uncle. Or so he says. Korine is known for making stuff up, but the stories that he tells are so absurd and fantastical that it doesn't matter if they're true or not. "I came to visit my uncle," he says. "He lives in a halfway house in Far Rockaway, and I guess last week some vandals broke in and stole all of his stuff. He had a huge comic book collection, and I guess most of it's gone, so he was freaking out. We went and drove a lot of comics to him to try and placate the situation. Where he lives in Far Rockaway is where they push most of the crazy people out. We were in a Chinese restaurant in this strip mall, and while my uncle was shoving lo-mien noodles down his throat, this black dude with like no teeth comes up to us and says 'You better make sure that baby is in her car seat.' And, you know, she's already sitting in the car seat…"

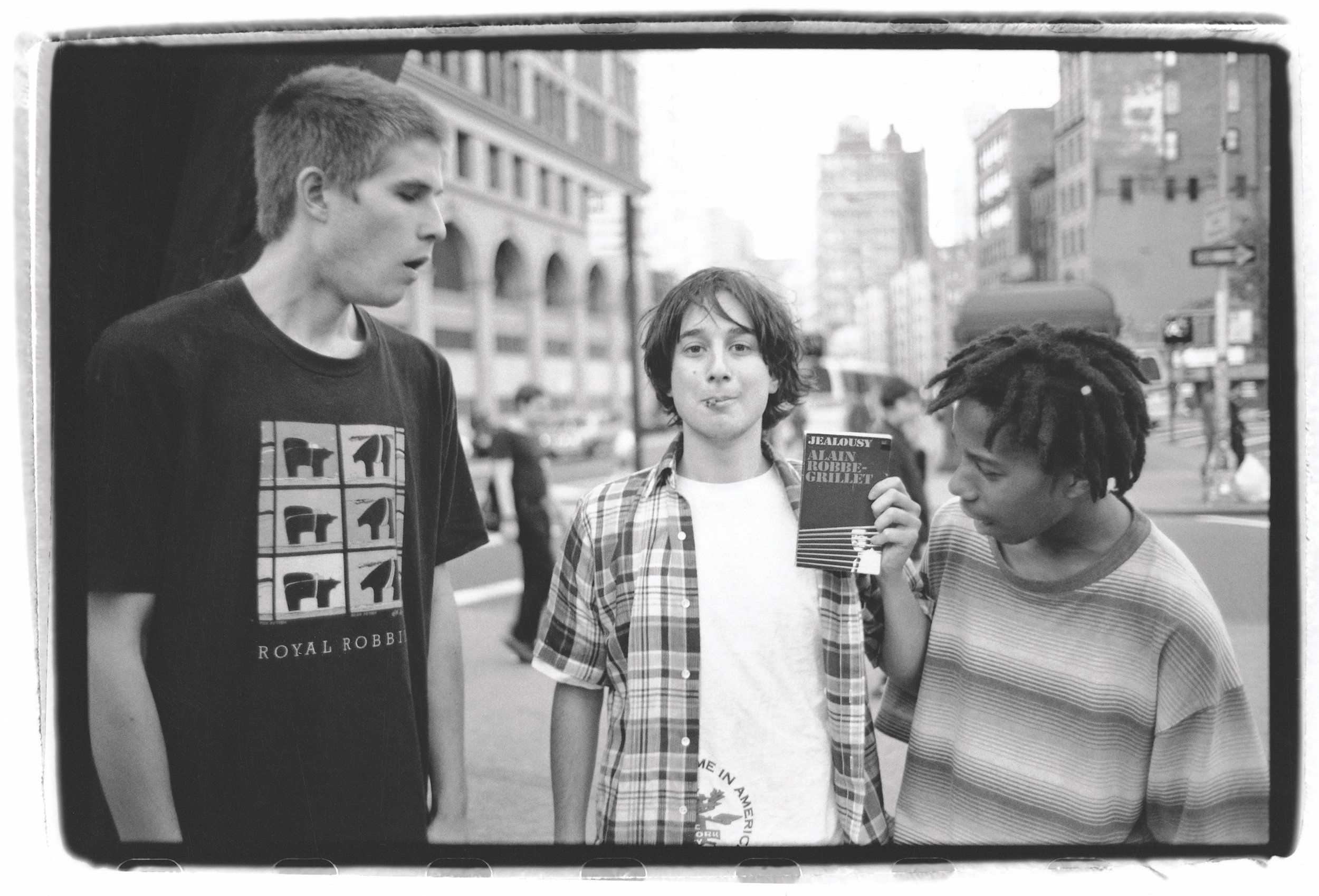

Korine first earned notoriety as the screenwriter of Larry Clark's controversial film Kids. Released in 1995, Kids was a day in the life of Manhattan teenagers, shocking at the time for its bleak depiction of adolescent drug use and sexuality. Instead of professional actors, Clark cast real New York kids such as Leo Fitzpatrick, Chloé Sevigny and Rosario Dawson, and the movie still stands as a depiction of what New York looked like before the bankers took over. Korine moved to New York the day after he graduated from high school and lived there for 10 years, but as much as he's associated with the city, he doesn't have much taste for it anymore. "I try to spend as little time here as possible," he says. About six or seven years ago, he left and moved back to his hometown of Nashville. "When I try to remember what I was thinking back then, it's very murky for me," he says. "But I was troubled and discombobulated. At a certain point, things just started to not add up. I just felt like there was a general sense of phoniness, and I was starting to enter a kind of paranoid state. I didn't feel like I had the anonymity that I wanted, so I started to withdraw and isolate myself. I didn't see the fun in it anymore. There wasn't much joy or humor."

Nashville wasn't his first choice, but it was the one that made the most sense. "I was pretty much debased having spent the better part of a decade living in the gutter, so when I got to Nashville, I was just kind of trying to recuperate. Kind of like a solider or something, I was just trying to get healthy again," he says.

In the late '70s and early '80s, Korine's father shot a PBS documentary series called South Bound, which profiled characters of the American South. "A lot of it had to do with rural music or moonshiners or circus people or kids who rode bulls in the rodeo," Korine recalls. "I would follow him around and there was this energy that I loved. Living in the carnival and selling goldfish was my favorite thing. You're forced to deal with these kind of characters that you usually would never see." This experience sparked a life-long love of both filmmaking and weirdos. Korine's films are decorated with eccentrics, from Bunny Boy, and Tummler's marvelous person, in Gummo to Trash Humpers, which features an amateur comedian who tells rambling gay jokes that lack a punchline, a boy preacher and incestuous fake siamese twins joined at the head by a pair of pantyhose, and the characters in his life are only marginally less fringe.

Up until about the age of 13, Korine wanted to be a tap-dancer. He took a few classes from "redneck whores who used to slap us across the face when we would get moves wrong," but what he really loved was the more freestyle, zany tap of dancers like the Nicholas Brothers and Sandman Jones. "I had these next door neighbors who were a year or two older than me and they were brothers, and they used to steal parking lot curbs and put them in their backyard," Korine says. "We would buy tap shoes and they would fill their back yard with these parking lot curbs and we would take the shoelaces out of our shoes and dance across the surface of the tops, trying to keep our feet from getting caught in the edges. We tried to invent this new style of tap dancing that was called 'curb dancing.' We would just curb dance after school and it was pretty great. Usually their dad would be BBQing and you would try to flip your shoe in mid-air and catch it again."

If that's not surreal enough, Korine continues. "And it's interesting, because their dad was one of the first guys to make money off the Choose Your Own Adventure novels," he says. "Both of the brothers ended up in prison. The oldest brother, Pepe, is on death row now and was going to get executed but was commuted to just life. And I went to visit him, and he had started writing these Choose Your Own Adventure novels that all take place in jail. He was trying to get me to see if I could get someone to publish it so that he could get commissary money. I bought him a couple of bags of Fritos and it made him more calm."

One of the most memorable scenes in Aaron Rose's 2007 film Beautiful Losers is when Korine stands in a Nashville playground and tells the story about how his friend was decapitated and the head found in that very spot, now full of frolicking children. "Hey, how you doin'?" Korine says to a little girl playing nearby, "You know, we found my friend Samuel's head there back in '86." "Cool!" she yells back, and Korine laughs and claps his hands.

I ask Korine if he seeks out these strange people, who hold even stranger stories. He doesn't know. "There are just a lot of them around me," he says. "Even just growing up, it didn't seem all that unusual. One of my closest friends from growing up was also sent to jail for backing his car over a kid's neck. Violence didn't even seem unusual. It just seemed like it was part of some vocabulary. It was just the way people expressed themselves, through violence or through vandalism. It just seemed like another mode of expression."

"I’ve seen Harmony’s work change dramatically and then at the same time not at all," Aaron Rose says. "While practice has certainly helped him to become a master of his medium, the themes that he is currently exploring in his work are not that different than the subjects that interested him when he was in his '20s. Harmony has always been attracted to the outsider. The freaks of humanity have always been the most beautiful people to him and I think you can see that as a throughline in all of his work."

In Trash Humpers, much like in Wall-E, words belong to the supporting players and the main characters communicate mostly in sounds: In this case guttural, noises, grunts and hideous shrieks of laughter. The most prolonged bit of dialogue from a trash-humper comes town the end of a film, in the form of a monologue delivered by Korine's character as he drives a car down a dark suburban street. "Sometimes when I drive through these streets at night, I can smell the pain of all these people living in there. I can smell how all these people are just trapped in their lives…And it hurts me to think that I live such a balanced life, and all these people, going to work, going to pray on Sundays…That's a stupid way to live…What people don't understand is that we choose to live like free people. We choose to live like people should live. I don't follow no rules on Sundays, I don't eat no pies on Monday, play no games on Tuesdays, I don't cry myself to sleep on Wednesday. It's all just one long game, I guess, and I suspect we'll win it. I suspect all these people will be dead and buried before I even catch my second wind…"

With Trash Humpers, Korine is holding a mirror up to the ugliest parts of society, but doing so not to shock or repulse, but because these are the parts that he likes the most. I once read an interview with him where he described America as a series of abandoned lots, and that's a viewpoint reflected quite clearly in Trash Humpers. "In some ways, I think it is the most beautiful thing: abandoned parking lots at night," he says. "Abandoned strip malls with couches around the edges, with spotlights overhead. I don't know. Maybe we just spend so much time in those places growing up, and it just seemed like that's all there was at a certain point. All there were were back alleyways and neon lamp-posts and dented stop signs and ditches with dead dogs and fucking ramshackle houses. That's just what America seemed like to me. Now, I notice people try to fix things up more, and try to like scrub the dirt away a little bit more," he continues. "I guess Trash Humpers in a way is, and these places that I kind of sought out were, more connected to this idea of what America looked like to me. Or what the South looked like, or maybe it was something even more below the surface—like what it felt like."

Korine explains Trash Humpers so eloquently than I begin to think I understand it. Then, I think about it so much that I start to doubt myself and am back where I began. It is, after all, a film about fucking garbage—how much is there to interpret, really? I ask Rose if he thinks we should try to "get" it. "Sure! Why not?" he says. "It’s pretty obvious if you’re willing to take your formulaic blinders off. The film speaks directly to our world and the human condition at the beginning of the 21st Century. People get wrapped up in the way a movie is “supposed to be” and forget that it’s totally cool to just watch something and accept it in the way it is being delivered. I think people are used to digesting culture as part of a prescribed formula. When it is offered up to them in a format they can understand they feel safe. I think this is one of the biggest tragedies of our age. The fact that there are 'right' ways to do everything. There is no right. There is no wrong. There is only vision...and Harmony has that in spades."

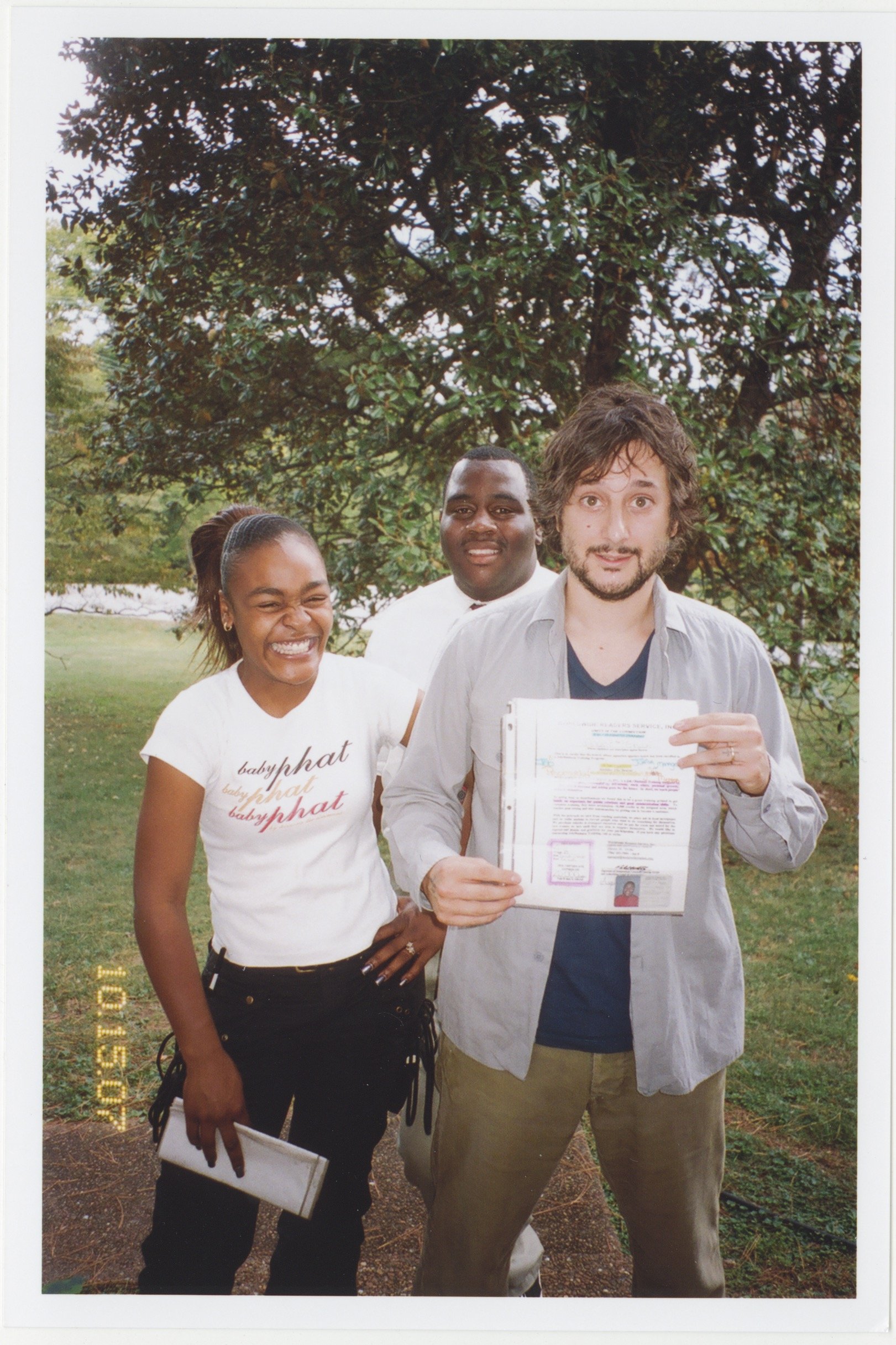

Trash Humpers is based on a series of photographs that Korine took of his assistant. "I would dress him up in these crude masks that looked kind of like a burn victim, and we would go out late at night and he would fornicate with trash or defecate on people's doorsteps or set things on fire," Korine says. "And I would use these really crude cameras, these disposable cameras, and take pictures of him. I started looking at them when we would get them developed, and I thought there was something there. There was something kind of creepy and exciting about the way they looked." The film was a very personal project, with Korine shooting most of it himself and his wife in one of the lead roles. Inexplicably, he says that "Trash Humpers is the product of having a baby." I ask why. "Because the baby was just three or four months when the idea came to me."

Korine and Rachel, his wife, have worked together before. First, in a Bonnie 'Prince' Billy video, when he put her in black face and a wedding dress, and in Mister Lonely, where she played Little Red Riding Hood. Rachel is beautiful and Korine describes her as "a great actress and really good physical mimic." They met in Nashville through a friend of a friend. "She was pretty young back then, she was just graduating high school," he says. "And I just thought she was amazing, so I tried to, like, talk to her." He laughs. "She wasn't that interested at the time."

I ask Korine if having a wife and child will now keep him from pursuing the type of projects he has in the past, like Fight Harm, a short film series where he would try to provoke bystanders into beating him senseless. "I could never pursue that particular project again, because my mind, I had to really be in a mental state that was really skewed. I was living completely like a tramp back then, so it's difficult to get in that head space," he says. "I don't really feel like having a kid has made me not enjoy those types of projects, but that particular one, I couldn't do again."

Other than that, he's not putting any restrictions on himself or anything he might want to do. Mister Lonely, which starred Diego Luna and Samantha Morton and was Korine's biggest-budget film to date, was reportedly a nightmare to get made, but that has not soured him on taking on more traditional projects. "I don't want to make a movie that was as difficult to put together as Mister Lonely, but in terms of scope, of course," he says. "I want to do everything. I like everything. I like big, small, in-between, torn-up, shredded, shit on…It's all good."

Korine just finished another script and is currently trying to cast it. It's a comedy or, as he corrects himself, "at least my version of a comedy." At this point, he's aware that not everyone shares his sense of humor. Fight Harm, which was abandoned after he was badly hurt several times and arrested, was also Korine's version of a comedy.

Korine grew up loving the comedy of Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers, and such films remain one of his biggest influences, however buried, and also perhaps the only key to an otherwise inexplicable oeuvre. "I remember the first time I saw Harpo [Marx] in one of those scenes where it is just like a five minute vignette of him playing the harp," Korine says. "There was something so beautiful about it, it was a poetry that transcended any kind of logic that all of a sudden for five minutes, Harpo would just play the harp in the middle of this movie. It was just incredible. It kind of changed my perspective on things, and the way I thought about things. I feel like Harpo is a big part of who I am. I thought that maybe, there's a kind of beauty in illogic... or there is something deep in this idea of nonsense."